- Home

- Raymond Kennedy

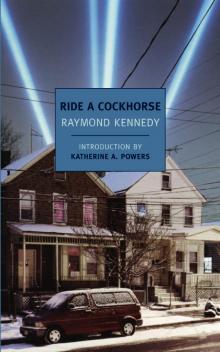

Ride a Cockhorse

Ride a Cockhorse Read online

RAYMOND KENNEDY (1934–2008) was born and raised in western Massachusetts. In 1982, he joined the creative writing faculty at Columbia University, where he taught until his retirement in 2006. Kennedy’s other novels include My Father’s Orchard; Goodnight, Jupiter; Columbine; The Flower of the Republic; Lulu Incognito; The Bitterest Age; and The Romance of Eleanor Gray.

KATHERINE A. POWERS’s column on books and writers ran for many years in The Boston Globe and now appears in The Barnes & Noble Review under the title “A Reading Life.” She is the editor of Suitable Accommodations: An Autobiographical Story of Family Life—The Letters of J. F. Powers, 1942–1963, forthcoming in 2013.

RIDE A COCKHORSE

RAYMOND KENNEDY

Introduction by

KATHERINE A. POWERS

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

Biographical Notes

Title Page

Introduction

Ride a Cockhorse

Dedication

Epigraph

REVOLUTION AT MAPLE AND MAIN

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

THE TERROR SPREADS

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

NIGHT OF DIRE RECKONINGS

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EXILE AND RETURN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

Copyright and More Information

INTRODUCTION

During the last decade or so of his life, Raymond Kennedy would occasionally and ceremoniously roll out of Brooklyn in his Lincoln Town Car and travel to western Massachusetts where I would see him now and again. He was drawn there by the countryside and the hill-and-valley towns of his youth, the region that provides the setting for all but one of his eight novels, including this one, his comic masterpiece. He told me that the most arresting memory of his childhood was seeing an enormous boat carried overland, progressing in state slowly and hugely past his house along Enfield Road near the Quabbin Reservoir. He was only five or six years old and stunned by its size and the surreality of its presence before him. It was, it turned out, a police boat bound for the recently completed reservoir whose supply of water for faraway Boston had submerged four little towns, including Enfield, the one toward which this road once traveled.

It is not likely that the breathtaking sight of this vessel on its way to preside over four drowned towns shaped Kennedy’s vision of the world, but it is just like him to recall it and its imperious journey with so much satisfaction. In his novels he is the master, usually celebratory, of the brazen, the impertinent and majestically presumptuous. And, as it happens, he liked especially to confer these qualities on his fictional women, creating as fantastic a bevy of dominatrixes as the world of letters has ever seen. From Flower of the Republic comes Pansy Truax, lubricious, titanic brawler, and Mrs. French, elderly, steely seductress; from Lulu Incognito, Mrs. Gansevoort, devourer of innocence, the very “flesh-and-blood epitome of a great destructive principle loosed upon earth”; and from this book, its turbulent heroine, Mrs. Frances “Frankie” Fitzgibbons.

Ride a Cockhorse, first published in 1991, is Kennedy’s sixth novel. It is set in the autumn of 1987 in a small city in Massachusetts’s Connecticut Valley where Mrs. Fitzgibbons, a widow and loan officer at a solid savings-and-loan bank, has gone mad, visited at the age of forty-five by sudden mania. Once kind, polite, and deferential, she is suddenly transformed into a powerhouse of ambition and a dynamo of sexual energy. She discovers in herself a “big thrilling voice,” astounding powers of eloquence, and radiant sexual magnetism; these she wields to persuade and persecute with unhinged abandon.

Mrs. Fitzgibbons is the managerial version of Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts; arbitrary and vindictive, she is never more truly her own megalomaniac self than when calling for somebody’s head. Her three-week reign of terror over the Parish Bank can be seen as a grotesque expression of the spirit that seized America in the 1980s, that of the ruthless downsizers and predatory takeover artists who annihilated jobs, and of the cavalier bankers who destroyed hundreds of savings-and-loan institutions. This wondrous, horrifying woman, amoral and insanely overreaching, is—as she herself might put it—all business. She revels in its buccaneer spirit, firing people willy-nilly, cutting multimillion-dollar deals, swiveling back and forth in her chair, “tossing out clichés in a quietly boastful manner.” She is sexually aroused by financial waffle and flimflam, by the celebration of innovation and audacity. Her short reign encompasses the stock-market crash of October 1987, whose furious disarray relieves her twinges of fear and paranoia: “The reality of what was happening to certain big corporations out there was perversely reassuring. The telephone in her fist felt like a weapon, like a heavy black hammer, something solid and useful.”

If Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s charade of being a banker is a satire on banking itself, especially as it broke loose from government regulation to ravage the land, her rise to power and demented, despotic rule can also be seen as a version of Hitler’s. That element is certainly there, handily inserted throughout in Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s denunciations and tirades, and as she gathers her select forces around her. Still, Ride a Cockhorse is the furthest thing from an allegory. It is surreal, certainly, but it is also firmly seated in its location, a small New England city very much like Holyoke, Massachusetts, the once-proud manufacturing town in which Kennedy spent a portion of his youth. He is fond of its people; they are his characters, and he describes their personalities, appearance, and little ways with wit and precision. And he rejoices in their speech: the novel is spangled with such venerable ornaments of American slang as “jamokes,” “galoots,” “welshers,” and “boogums.”

We can detect, amid the comedy and verbal pyrotechnics, the author’s nostalgic regret that American cities have lost their dignity. The Parish Bank, after all, is located on what was once the city’s business main street: now no longer the self-respecting thoroughfare of its hey-day but “revitalized” as an open-air mall. The atmosphere of a little burg’s traditional amour propre pervades the novel, and, in fact, the floodgates of Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s mania are opened by those stirring expressions of American civic pride: the high-school marching band and the triumphal, neoclassical architecture of banks of yore.

Kennedy’s depictions of the bank’s interior and of the marching band are exhilarating and, in the case of the latter, peerlessly so. The pages devoted to the rousing, uniformed splendor of the band as it comes swinging around the corner transmit to our own spirits a giddiness and buoyancy almost equal to that which infects the newly volatile Mrs. Fitzgibbons:

The spectacle overall, with its American flags and high school colors flying, its brilliant purple ranks and gleaming brass, exceeded description—as in the way, for example, that it turned the corner at Essex and Locust, with the inside marchers marking time very smartly, their knees snapping up and down in place, while the entire rank pivoted round them like a swinging dial, and then stepping forth proudly again, raising their horns to their lips. To Mrs. Fitzgibbons, the music and grand moving panoply of it all was nothing short of celestial, as though the Maker was showing His minions.

At the head of this magnificent assemblage is the “resplendent young drum major,” eighteen-year-old Terry Sugrue; it is he, this “vision of martial beauty,” who has unleashed the middle-aged widow’s libido:

His head was up; he had a brass whistle in his mouth; the sun was in his face. Behind him,

the row of majorettes had followed suit, their bare knees and white boots flashing up and down in perfect synchronicity with his own steps. The golden tassels of his prodigious baton blew and shimmered in the October air. Mrs. Fitzgibbons had an impulse to run into the street and wrestle him to the pavement. Suddenly the drums fell silent, the boy’s whistle pierced the air, up shot the baton, there was a great clash of cymbals, and twenty trumpets sounded in unison ...

“I’d like to change his diapers,” said Mrs. Fitzgibbons.

Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s iron-fisted seduction of this young man is only the first of her conquests. At the bank, energized by madness, the formerly mild-mannered employee finds her unfettered spirit in towering accord with the building’s interior, the “great marble-columned room, ... a magnificent, high-vaulted emporium, with its venerable dimensions, its twinkling dome, the long row of golden grilles of the tellers’ windows—an almost celestial hall!” She usurps command through sheer willpower: it shimmers from her electrified presence and makes itself heard in vituperative riffs and wild fulminations, a heady verbal excess in which her creator clearly takes as much pleasure as she does.

She’s got style. Bold, charismatic, and conquering, she moves up from a pitiful Honda to an enormous Buick commandeered from her hairdresser’s boyfriend, Matthew, who enlists himself as her driver. With him at the wheel, the fabulous, frightening Mrs. Fitzgibbons travels big, her acolytes following behind in another car of despicable inconsequence: “The sight of the filthy compact following Matthew’s gleaming, highly polished Buick down Dwight Street toward the business district was curious to the eye. It looked as though the Buick had snagged something under its wheels and was towing it to the city dump.”

Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s manic transformation into a juggernaut, ghoulishly funny as it is, is not entirely an antic affair; she is, in the first place, a genuine destroyer, gloating over the lives she ruins. Kennedy paints distressing pictures of those victims, their jobs annihilated by a force beyond reason or control. But then there is the case of Mrs. Fitzgibbons herself: she is tragically mentally ill. At times she glimpses this, feeling that she cannot quite control her thinking, at one juncture experiencing “the odd sensation that her brain had actually contracted; that the scope of her thinking was somehow attenuated, like water jetting from a nozzle.” It must all end badly—in a macabre sexual Götterdämmerung. But when it does, and when the sun has finally set on Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s regime, the novel finishes on an unexpected note of pathos that is truly moving.

Ride a Cockhorse is a brilliant, all-American oddity and its author, a one-man band. Somehow in these pages Kennedy has brought together surrealism, satire, and black comedy; affection, empathy, and nostalgia; astute characterization, inspired description, and astonishing linguistic brio. To quote Mrs. Fitzgibbons in a moment of sexual exultation: “This is the goods!”

—KATHERINE A. POWERS

RIDE A COCKHORSE

For Charles Drapeau

Ride a cockhorse to Banbury Cross

To see a fine lady on a white horse.

With rings on her fingers and bells on her toes,

She shall have music wherever she goes.

REVOLUTION AT MAPLE AND MAIN

ONE

Looking back, Mrs. Fitzgibbons could not recall which of the major changes in her life had come about first, the discovery that she possessed a gift for persuasive speech, or the sudden quickening of her libido. While the latter development was the more memorable of the two, involving as it did the seduction of young Terry Sugrue, the high school drum major, it was Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s newfound ability to work her will upon others through her skills with language which produced the most exciting effects. By early fall, some of her fellow workers at the Parish Bank, where Mrs. Fitzgibbons was employed as a home loan officer, could not have helped noticing her growing assertiveness on the job. She was ordinarily very reasonable and sweet-tempered, the soul of polite discretion. Almost overnight, she had become more strident, even to the point of badgering customers on the telephone and lifting her voice to a level that was considered inconsistent with the usual soft-spoken manner of a courteous banker. She could also be quite tart and provocative with those working around her, as on the afternoon when she lectured Connie McElligot, the woman at the next desk, for fifteen minutes on the subject of how the escalating interest rates of the 1980s portended an economic crisis of global proportions. Moreover, while speaking, Mrs. Fitzgibbons let fall certain locutions that revealed her true feelings toward the other woman, which were deprecative and of long standing, as she likened Connie McElligot’s ignorance of such perils to that of any layman walking in from the street. “What would you know about the connection between interest rates at the Fed and the collapse of commodity prices in South America?” she said. “Nothing. Not word one.”

It was during these same days precisely, however, in the early fall, that Mrs. Fitzgibbons developed an unexpectedly lustful interest in the resplendent young drum major who led the high school band past her house. Every Saturday morning, at fifteen minutes to twelve, the big noisy ensemble came round the corner of Essex Street, not a hundred feet from her door, with flags and pennants blowing and the tall, sandy-haired Sugrue boy out front, high-stepping his way into view. It was a sight to behold. He flourished an enormous gold-tasseled baton. With his high purple hat, his fringed epaulets, and great chestful of gleaming brass buttons, he offered a vision of martial beauty. Behind the young drum major, like an amplification of his own youthful grandeur, came the band in perfect step, a colorful machine. First were the three flag bearers, followed by a gorgeous rank of prancing, bare-thighed, arrogant-looking majorettes, their batons twirling in unison in the sun. A half dozen cheerleaders followed, in purple-and-white sweaters, shaking pom-poms in both hands, and, last of all, the big, solid eighty-piece marching band itself, with trumpets and snare drums going. The sound was deafening. The spectacle overall, with its American flags and high school colors flying, its brilliant purple ranks and gleaming brass, exceeded description—as in the way, for example, that it turned the corner at Essex and Locust, with the inside marchers marking time very smartly, their knees snapping up and down in place, while the entire rank pivoted round them like a swinging dial, and then stepping forth proudly again, raising their horns to their lips. To Mrs. Fitzgibbons, the music and grand moving panoply of it all was nothing short of celestial, as though the Maker were showing off His minions.

Unfortunately, Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s married daughter, Barbara, who often visited her mother on Saturday mornings, took an altogether different view of the noisy, militaristic display parading past in the street. Barbara Berdowsky was a person very much up to the minute in her social views, and in her manner of expressing herself associated a coarse tongue with the language of feminist liberation, environmentalism, and other such current enthusiasms. “They look like a bunch of fucking Nazis,” she said.

Mrs. Fitzgibbons had not heard, however, as at that moment she was standing behind the leafy curtain of Dutchman’s-pipe that ornamented her front porch, staring fixedly at the lean ramrod figure of the drum major himself. Terry Sugrue had halted smartly right in front of her house, holding his baton on a high diagonal from his chest, to signify, no doubt, the introduction of a new musical piece. He was marching in place. His head was up; he had a brass whistle in his mouth; the sun was in his face. Behind him, the row of majorettes had followed suit, their bare knees and white boots flashing up and down in perfect synchronicity with his own steps. The golden tassels of his prodigious baton blew and shimmered in the October air. Mrs. Fitzgibbons had an impulse to run into the street and wrestle him to the pavement. Suddenly, the drums fell silent, the boy’s whistle pierced the air, up shot the baton, there was a great clash of cymbals, and twenty trumpets sounded in unison.

In tempo with the vigorous diagonal strokes of the drum major’s baton, the band came past Mrs. Fitzgibbons’s house. The noise was breathtaking. The drumming was indescr

ibable. The purple-and-white uniforms lit up. The musical selection chosen by the bandmaster, Mr. Pivack (who wore a special beige-and-cream uniform and habitually skipped about on one side or the other of his talented assembly), became recognizable to the ear. It was the high school’s own football fight song. Mrs. Fitzgibbons kept her eyes fixed all the while on the vain young drum major, as he high-stepped his way up the tree-flanked roadway toward the Franklin Street football field. The music was so loud that Barbara didn’t hear her mother’s remark, obliterated as it was by the grunting of the tubas going past. “I’d like to change his diapers,” said Mrs. Fitzgibbons.

She never knew what had come over her, nor was she much inclined to think about it, but for a week running, Mrs. Fitzgibbons dressed up for herself every night and went riding in her car. One evening, before going out, she caught an unexpected glimpse of herself in the hall mirror and was delighted to discover a stranger looking back at her. She was wearing the dark violet Charmeuse dress that she had worn to her daughter’s wedding, and had accessorized with the silver and amethyst choker that her late husband, Larry, had given her one Christmas; her hair was tied back, and her face made up with obvious skill; even the lift of her own breasts struck Mrs. Fitzgibbons as the attraction of someone else. For more than an hour that evening, she drove around town in her dented Honda; she had the windows down and was listening to the Top 40 on the radio. It was the car that Larry had bought for them back in 1982, two years before he died. “Everybody thinks that the Chinese make junks,” he used to say, “but the Japanese made this one.” (Larry was witty. Mrs. Fitzgibbons never denied him that. On his deathbed, when he knew he was finished, he smiled at her, and said, “What were my last words?” That was Larry’s farewell. He never spoke again.)

Ride a Cockhorse

Ride a Cockhorse